“They have an engine called the Press whereby the people are deceived.”

From “That Hideous Strength”, by C.S. Lewis, 1945

It was research into salmon in Alaska on Don Croft’s Etheric Warriors forum, I’m guessing in maybe 2015, which broke the game open for me.

Specifically, it was recognizing that the salmon population in the Pacific was decreasing due to the Death energy from World Wars one and two.

I don’t think the post survived the spook cleanout of the database, which removed much or most of my really impactful material. If anyone knows that it’s there, please send me a note.

This newest, broadest analysis of salmon in the Pacific involves Bristol Bay, Alaska and the Mokelumne River in Northern California.

There are a number of breakthroughs in it, namely proof of simultaneous technology-driven species decimation of two different salmon populations, along with an analysis of the hilarious propaganda rebutting that thesis.

Once all of the data which I have compiled over the last eleven years of this research has been pulled into a single database, and tagged, it will be child’s play to prove my thesis. For example, just laying “Billfish” down on top of “Salmon” will reveal more connections, more proofs.

However, I’m doing this manually, one article at a time, and must be content with the progress which I have made thus far.

THE DATA

In 1864, top telegraph company Western Union operated on 44,000 miles of wire and was valued at $10 million. Within the next year, its worth had jumped to $21 million. It is estimated that between 1857 and 1867 the company’s value grew by 11,000 percent. In 1866, its network included about 100,000 miles of wire and its capital stock value was in excess of $40 million.

On March 7, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell developed the world’s first working telephone.

From 1893 to 1894, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 31.3%, from 940,000 to 1,235,400.

In 1893, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 940,000.

From 1894 to 1895, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 19.2%, from 1,235,400 to 1,472,137.

In 1894, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 1,235,400.

From 1895 to 1896, the 40.1% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 109% greater, or more than twice as great as its 19.2% increase from 1894 to 1895.

The reproductive rate of salmon in Alaska is increasing exponentially, going forward in time.

From 1895 to 1896, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 40.1%, from 1,472,137 to 1,999,740.

In 1895, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 1,472,137.

From 1896 to 1897, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 65.9%, from 1,999,740 to 3,317,523.

From 1896 to 1897, the 65.9% increase in size of the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 64.3% greater than its 40.1% increase from 1895 to 1896.

The reproductive rate of salmon in Alaska is continuing to increase exponentially, going forward in time, albeit at a slightly slower rate (with positive variances of 109%, then 64.3%)

In 1896, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 1,999,740.

From 1897 to 1898, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 48.5%, from 3,317,523 to 4,927,840.

In 1897, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 3,317,523.

From 1898 to 1899, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 3.8%, from 4,927,840 to 5,112,737.

In 1898, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,927,840

From 1899 to 1900, the 67.2% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 1,668.4% greater than its 3.8% increase from 1898 to 1899.

This positive variance is 1,430% greater than the 109% positive variance from 1895 to 1896, versus 1894 to 1895.

From 1899 to 1900, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 67.2%, from 5,112,737 to 8,547,335.

In 1899, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 5,112,737.

From 1900 to 1901, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 19.2%, from 8,547,335 to 10,220,577.

In 1900 the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 8,547,335.

From 1901 to 1902, the 25.3% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 31.7% greater than their 19.2% increase from 1900 to 1901.

The reproductive rate of salmon in Alaska is continuing to increase exponentially, going forward in time, albeit at a slightly slower rate (with positive variances of 109%, then 64.3%, then 31.7%, calculate rate - the force that is decreasing the fertility of the salmon in Alaska is getting stronger, going forward in time.)

From 1889 to 1900, the positive variance versus 1898 to 1899 was 1,668.4%. The next year, from 1900 to 1901, the positive variance versus the previous year decreased by 98%, to 31.7%. Then, from 1902 to 1903, the positive variance versus the previous year decreased by 78.3%, to 8.3%.

What influence so negatively impacted the salmon in Bristol Bay, Alaska from 1899 to 1903?

In 1895, a young Italian named Gugliemo Marconi invented what he called “the wireless telegraph” while experimenting in his parents’ attic. He used radio waves to transmit Morse code and the instrument he used became known as the radio.

In 1898, the Spanish-American War ended Spain’s colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere and secured the position of the United States as a Pacific power.

On December 23, 1900, the Canadian inventor Reginald A. Fessenden became the first person to send audio (wireless telephony) by means of electromagnetic waves, successfully transmitting over a distance of about a mile (1.6 kilometers).

From 1901 to 1902, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 25.3%, from 10,220,577 to 12,808,515.

In 1901, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 10,220,577.

From 1902 to 1903, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 27.4%, from 12,808,515 to 16,320,092.

From 1902 to 1903, the 27.4% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 8.3% greater than its 25.3% increase from 1901 to 1902.

In 1902, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 12,808,515.

From 1903 to 1904, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 27%, from 16,320,092 to 11,903,352.

Here, from 1903 to 1904, we have the first decrease in salmon in Bristol Bay in history, and it is huge. A one-third decrease in population, after a negative impact which began three or four years earlier, in 1900 to 1901.

In 1903, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled an all-time high 16,320,092.

From 1904 to 1905, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 24.6%, from 11,903,352 to 14,833,989.

In 1904, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,903,352.

From 1905 to 1907, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 31.3%, from 14,833,989 to 10,193,403.

From 1905 to 1906, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 27%, from 14,833,989 to 10,823,431.

From 1903 to 1904 and from 1905 to 1906, the 27% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay salmon were identical.

The reproductive rate of salmon in Alaska being driven down at a fixed rate, going forward in time.

Here, in 1903, we see the first population decreases in the data set. The force that was previously decreasing the fertility at an ever-greater rate is now powerful enough that it is driving population numbers downward and backward.

In 1905, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 14,833,989.

From 1906 to 1907, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 5.8%, from 10,823,431 to 10,193,403.

In 1906, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 10,823,431.

From 1907 to 1908, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 59.3%, from 10,193,403 to an all-time high 16,233,802.

This is the second largest one-year increase in the data set, not far below the 65.9% increase nine years earlier, from 1896 to 1897, from 1,999,740 to 3,317,523.

If my theory that the vibrational rate of the Earth and the health of the ether are increasing heading toward 2012 and beyond, here we can see that improvement in health staying ahead of the nascent technologies of the times’ ability to degrade it and hold it back.

In 1907, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 10,193,403.

From 1908 to 1911, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 45.7%, from 16,233,802 to 8,815,114

From 1908 to 1911, 47.5% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 51.8% greater than its 31.3% decrease from 1905 to 1907.

Here, from 1908 to 1911, some negative influence is getting stronger.

The electrical grid is expanding with the construction of every city, town and village. Radio is sweeping the world, pouring purportedly-harmless radiation into the ether, and exponentially driving down the fertility of salmon in Alaska.

From 1908 to 1909, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 4.5%, from 16,233,802 to 15,497,883.

In 1908, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 16,233,802.

From 1909 to 1910, the 25.2% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 460% greater than its 4.5% decrease from 1908 to 1909.

Here, in 1910, the force that is decreasing the fertility of salmon in Alaska with ever-greater effectiveness is at its greatest strength yet documented.

From 1909 to 1910, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 25.2%, from 15,497,883 to 11,593,609.

In 1909, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 15,497,883.

In 1910, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,593,609.

From 1911 to 1912, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 123.5%, or well more than doubled, from 8,815,114 to an all-time high 19,696,343.

This staggering population explosion of salmon in Alaska from 1911 to 1912 is the largest in the data set. It is 87.4% greater, or almost double the second-largest, which was the 65.9% increase from 1896 to 1897, when the catch increased from 1,999,740 to 3,317,523.

In 1912, the commercial catch of 19,696,343 chinook salmon in Bristol Bay, Alaska was 494% greater, or six times greater than the 3,317,523 salmon caught fifteen years earlier, in 1897.

The improvement in health of the ether is far greater than the collectively ability of technology at that time to hold it back.

In 1911, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 8,815,114

From 1912 to 1913, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 4.5%, from 19,696,343 to 20,581,826.

In 1912, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled an all-time high 19,696,343, which was 20.7% greater than the previous all time high of 16,320,092 in 1903.

From 1913 to 1914, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 1.9%, from 20,581,826 to 20,195,107.

In 1913, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled an all-time high 20,581,826.

In 1913, the all-time high commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon of 20,581,826 was 4.8% greater than the previous all-time high of 19,696,343 from 1912.

From 2014 to 2015, the 26.9% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 1,316% greater than its 1.9% decrease from 1913 to 1914.

From 2014 to 2015, the 1,316% positive variance in the decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1913 to 1914 was 186% greater, or almost three times greater the 460% positive variance in that decrease from 1909 to 1910 versus 1908 to 1909.

The force that is decreasing the fertility of salmon in Alaska is getting stronger, and ever-stronger. Here we see the health of the ether degraded not only the ever-increasing expansion of radio, the telephone, electricity, et al, but also the Death energy from World War I, which commenced in 1914.

From 1914 to 1915 the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 26.9%, from 20,195,107 to 14,767,678.

In 1914, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 20,195,107.

From 1915 to 1917, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 66%, from 14,767,678 to an all-time high 24,512,532,

From 1915 to 1916, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 18.7%, from 14,767,678 to 17,521,921.

In 1915, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 14,767,678.

From 1916 to 1917, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 39.9%, from 17,521,921 to 24,513,532.

In 1916, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 17,521,921.

In 1917, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled an all-time high 24,513,532.

In 1917, the 19.1% positive variance of the all-time high Bristol Bay sockeye salmon total vs. 2013 was 298% greater, or four times greater than the 4.8% positive variance in 1913 vs. 1912.

Here, in 2017, the population of salmon in Bristol Bay, Alaska is nearly vibrant, the largest in history.

From 1917 to 1919, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 71.8%, from an all-time high 27,513,532 to 7,761,375.

From 1917 to 1919, the 71.8% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 166.9% greater than its 26.9% decrease from 1914 to 1915.

This is clearly driven largely by Death energy from World War I.

From 1917 to 1918, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 16%, from an all-time high 27,513,532 to 23,090,665.

In 1917, the all-time high catch of 24,513,532 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 19.1% greater than the previous all-time high of 20,581,826 in 1913.

From 1918 to 1919, the 66.4% decrease in the commercial catch of BristolBay sockeye salmon was 315% greater, or more than four times greater than its 16% decrease from 1917 to 1918.

This is clearly driven largely by the Death energy from World War I.

From 1918 to 1919, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 66.4%, from 23,090,665 to 7,761,375.

In 1918, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 23,090,665.

From 1919 to 1922, the 192% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 190% greater, or almost three times greater than its 66% increase from 1915 to 1917.

Here, with the removal of the Death energy from World War I from the equation, the health of the ether is improving at a rate exponentially greater than that of technology’s ability to degrade it. The reproductive strength of the salmon in Alaska has never been greater.

From 1919 to 1922, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 192%, or nearly tripled, from 7,761,375 to 22,632,077.

From 1919 to 1920, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 14.6%, from 7,761,375 to 8,897,915.

In 1919, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,761,375.

From 1920 to 1921, the 76.2% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 422% greater than its 14.6% increase from 1919 to 1920.

From 1920 to 1921, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 76.2%, from 8,897,915 to 15,680,076.

From 1920 to 1921, the 422% positive variance in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon vs. 1919 to 1920 was 4,984% greater than the 8.3% positive variance in 1903 to 1904 vs. 1901 to 1902.

After being decimated by the Death energy of World War I, salmon in Alaska are reproducing at the highest level in history once again by 1921.

In 1920, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 8,897,915.

From 1921 to 1922, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 44.3%, from 15,680,076 to 22,632,077.

In 1921, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 15,680,076.

From 1922 to 1926, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 16.6%, from 23,632,077 to 19,710,000.

From 1922 to 1925, the 68.4% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 4.7% less than its 71.8% from 1917 to 1919.

The health of the ether is improving again after absorbing that great amount of Death energy from World War I.

From 1922 to 1925, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 69.7%, from 23,632,077 to 7,161,375.

From 1922 to 1923, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 23%, from 23,632,077 to 18,181,964.

In 1922, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 23,632,077.

From 1923 to 2024, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 43.4%, from 18,181,964 to 10,302,066.

In 1923, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 18,181,964.

From 1924 to 1925, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 30.5%, from 10,302,066 to 7,161,375.

In 1924, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 10,302,066.

From 1925 to 1926, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 171%, or almost tripled, from 7,161,375 to 19,414,094.

From 1925 to 1926, the 171% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 10.9% less than its 192% increase from 1919 to 1922.

This is evidence of radio, electricity, telephones and the telegraph degrading the health of the ether.

In 1925, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,161,375.

From 1926 to 1927, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 42.9%, from 19,414,094 to 11,071,828.

In 1926, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon 19,414,094.

From 1927 to 1928, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 78%, from 11,071,828 to 19,710,000.

From 1927 to 1928, the 78% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 54.4% less than its 171% increase from 1925 to 1926.

From 1927 to 1928, the 54.4% negative variance in the increase of the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1925 to 1926 was 399% greater, or five times greater than the 10.9% negative variance in same from 1925 to 1926 versus 1919 to 2022.

This is evidence of radio, electricity, telephones and the telegraph degrading the health of the ether.

In 1927, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,071,828.

From 1928 to 1930, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 78.4%, from 19,710,000 to 4,259,188.

From 1928 to 1930, the 78.4% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 14.6% greater than its 68.4% decrease from1922 to 1925.

Radio, telephones, electricity and the telegraph are degrading the health of the ether with ever-increasing speed.

From 1928 to 1929, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 38.1%, from 19,710,000 to 12,188,648.

In 1928, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 19,710,000.

From 1929 to 1930, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 65%, from 12,188,648 to 4,259,188.

In 1929, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 12,188,648

In 1930, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon 4,259,188. That’s the lowest since 1897’s total of 3,317,523. Since there were far more fishing vessels in Alaska in 1930 than the fourth year of record keeping in 1897, we can see that the salmon in Bristol Bay, Alaska has been suddenly decreased to near-extinction here in 1930.

And Americans were too busy listening to the Amos and Andy radio program to notice.

From 1930 to 1933, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 457%, from 4,259,188 to 23,708,950.

From 1930 to 1933, the 486% positive variance of the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1927 to 1928 was 10.9% greater than the 422% positive variance in in 1920 to 2021 versus 1919 to 1920.

The see-saw battle between technology and the ever-increasing health of the ether continues.

From 1930 to 1931, the 457% increase in the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon was 486% greater, or almost six times greater than its 78% increase from 1927 to 1928.

From 1931 to 1932, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 16.8%, from 12,790,614 to 14,939,552.

In 1931, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 12,790,614.

From 1932 to 1933, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 58.7%, from 14,939,552 to 23,708,950.

In 1932, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 14,939,552.

From 1933 to 1935, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 87.3%, from 23,708,950 to 3,022,599.

From 1933 to 1935, the 87.3% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was % greater than its 78.4% decrease from 1928 to 1930.

From 1933 to 1934, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 13.1%, from 23,708,950 to 20,600,510.

In 1933, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 23,708,950.

In 1934, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 20,600,510.

From 1935 to 1940, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 56.4%, from 3,022,599 to 4,726,687.

This is low-year to low-year.

In 1935, the commercial catch of 3,022,599 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was the fifth lowest in history, and 8.9% less than the 3,317,523 salmon caught in the fifth salmon season on record in 1897.

In 1935, the commercial catch of 3,022,599 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 29% less than the 4,259,188 caught in 1930.

The poisoning of the ether by Radio, telephones, electricity and the telegraph is driving the fertility of salmon in Alaska down ever further.

From 1935 to 1938, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 684%, or by almost seven times, from 3,022,599 to 23,708,950.

From 1935 to 1938, the 684% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 27.1% greater than its 457% increase from 1930 to 1933.

From 1935 to 1938, the 27.1% positive variance in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1930 to 1933 was % less than the 486% positive variance in 1930 to 1931 versus 1927 to 1928.

From 1935 to 1936, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 581%, from 3,022,599 to 20,586,884.

From 1935 to 1936, the 581% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 94.4% less than its 457% increase from 1930 to 1933.

In 1935, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 3,022,599.

From 1936 to 1937, the 3.3% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 99.4% less than its 581% increase from 1935 to 1936.

From 1936 to 1937, the 99.4% negative variance in the increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1935 to 1936 was 5.3% greater than the 94.4% negative variance from 1935 to 1936 versus 1930 to 1933.

From 1936 to 1937, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 3.3%, from 20,586,884 to 21,257,814.

In 1936, World War II began.

In 1936, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 20,586,884.

In 1937, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 21,257,814.

From 1938 to 1942, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 74.3%, from 24,699,788 to 6,343,363.

From 1938 to 1942, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by an annual average of 18.6%.

From 1938 to 1940, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 80.8%, from 24,699,788 to 4,726,687.

From 1938 to 1940, the 80.8% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 7.7% less than its 87.5% decrease from 1933 to 1935.

Here, even up to 1940, the game is going in the right direction, is inexorably improving, despite the ongoing degradation of the ether. That’s because the vibrational rate of the Earth is increasing, heading toward 2012 and beyond, and the health of the ether is increasing right along with it.

From 1938 to 1939, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 46%, from an all-time high 24,699,788 to 13,322,345.

From 1938 to 1943, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by an annual average of 5.5%.

From 1938 to 1943, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 23.7%, from 22,699,788 to 17,330,218. These were both high years.

This clearly documents the deleterious effect of the Death energy from World War II on the fertility of salmon in Alaska.

In 1938, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 24,699,788. This was a high year.

In 1938, the 24,699,788 commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 4.1% greater than the 23,708,950 salmon caught in 1933.

Here, in 1938, the increasing health of the ether and the Earth’s vibrational rate are still progressing more quickly than technology’s ability to degrade them.

From 1939 to 1940, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 64.5%, from 13,322,345 to 4,726,687.

From 1939 to 1940, the 64.5% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 126% greater, or more than twice as great as its 29% average annual decrease from 1943 to 1945.

This directly refutes alaska.gov’s false claim that “the Egegik District has demonstrated relatively stable production through its history, except for a period related to World War II when fishing effort was down.”

Alaskan salmon fishermen would not have slackened their efforts until 1941, when the United States entered World War II.

In 1939, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 13,322,345.

From 1940 to 1941, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 51.5%, from 4,726,687 to 7,153,704.

In 1940, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,726,687. This was a low year.

From 1941 to 1942, the 11.3% decrease in the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon was 442% less than the 3.3% increase from 1936 to 1937.

1935 and 1940 were both “low” years. This statistic measures two years out from the low.

The Death energy created by World War II is degrading the fertility of salmon in Alaska to a degree never witnessed previously. And this includes not only Death energy released by murdered humans, but also the nascent technology of Radar.

Or you could go with alaska.gov’s version, which is “The Egegik District has demonstrated relatively stable production through its history, except for a period related to World War I1 when fishing effort was down.”

Where “down” is general. As you may recall, generality is a hallmark of propaganda.

From 1936 to 1937, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 3.3%, from 20,586,884 to 21,257,814.

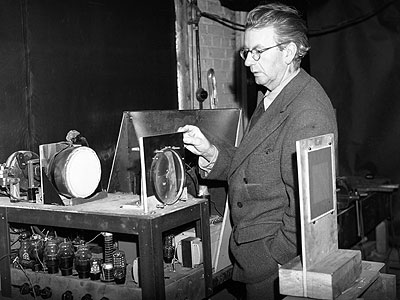

(Scottish Rite Freemason John Logie Baird, with the first color television, Scotland, 1937. Take note of how the image focuses on his left eye.)

The image is constructed to focus attention on his left eye because, to generational Satanist Freemasons like Mr. Baird, the left eye is the “eye of Will” or the “eye of Horus”.

But don’t take my word for it:

‘The right eye is the Eye of Ra and the left is the Eye of Horus’.”

From “Freemasonry - Religion And Belief - The 3rd Temple”

Facebook: “Welcome to the Left-Hand-Path-Network, where Satanism is not about worship, but it’s study.”

I have included John Logie Baird’s picture so that you could get a better idea of what a generational Satanist Freemason in a position of fairly significant influence looks like.

He figured that the rubes would never notice the coded visual imagery.

It’s not like these people aren’t right up front about what they’re doing, and what they’re into.

We’ve just been conditioned, over literally Millennia, not to “notice” it.

Generational Satanists are all related to one another through the maternal bloodline. They comprise between twenty and thirty percent of the populace, and are hiding in plain sight in every city, town and village on Earth.

It’s how the few have controlled the many all the way back to Babylon, and before.

But they say that the hardest part of solving a problem is recognizing that you have one.

Don Croft used to say “Parasites fear exposure above all else”.

How long do you think that these people have left in power, now?

Please consider doing what you can to help speed the transition.

From 1941 to 1942, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 11.3%, from 7,153,704 to 6,343,363.

In 1941, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,153,704.

From 1942 to 1943, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 173.2%, from 6,343,363 to 17,330,218.

In 1942, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 6,343,363.

From 1943 to 1945, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 57.9%, from 17,330,218 to 7,300,247.

From 1943 to 1945, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by an annual average of 29%.

From 1943 to 1944, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 33.4%, from 17,330,218 to 11,545,604.

In 1943, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 17,330,218. This was a high year.

From 1944 to 1945, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 36.7%, from 11,545,604 to 7,300,247.

In 1944, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,545,604.

From 1945 to 1946, the 16.5% increase in the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon was 90.5% less than its 173.2% increase from 1942 to 1943.

This directly refutes alaska.gov’s bald-faced lie that “The Egegik District has demonstrated relatively stable production through its history, except for a period related to World War II when fishing effort was down.”

Here, from 1945 to 1945, we should see a whole bunch of soldiers returning from World War II and getting back to harvesting the rested-up salmon in Alaska by the ton. Yet we see precisely the opposite.

That’s because the truth is that the Death energy from World War II is continuing to poison the ether and decimate the salmon population in Alaska, as demonstrated by this statistic.

From 1945 to 1946, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 16.5%, from 7,300,247 to 8,501,206.

In 1945, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,300,247. This was a low year.

From 1946 to 1947, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 119.3%, from 8,501,206 to 18,642,208

In 1946, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 8,501,206 to 18,642,028.

From 1947 to 1948, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 22%, from 18,642,028 to 14,544,389.

From 1947 to 1948, the 22% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 34.1% less than the 33.4% decrease from 1943 to 1944.

The magnitude of the decrease is the salmon harvest is lessening as the Death energy from World War II continues to be removed from the equation, going forward in time.

In 1947, the high-year count of 18,642,028 sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay was 7.6% greater than the 17,330,218 caught in high-year 1943.

With the end of World War II, the natural environment quickly begins to recover.

From 1947 to 1951, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 76.8%, from 18,642,028 to 4,326,543.

From 1947 to 1949, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 65.9%, from 18,642,028 to 6,343,363.

In 1947, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 18,642,028. This was a high year.

From 1948 to 1949, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 56.4%, from 14,544,389 to 6,343,363.

In 1948, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 14,544,389.

From 1949 to 1950, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 13.1%, from 6,343,363 to 7,175,275.

In 1949, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 6,343,363.

From 1950 to 1951, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 39.7%, from 7,157,275 to 4,326,543.

In 1950, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,157,275.

From 1951 to 1952, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 160.4%, from a low-year 4,326,543 to 11,266,129.

From 1951 to 1952, the 160.4% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 34.5% greater than its 119.3% increase from low-year 1946 to 1947.

The ether continues to recover, as the vibrational frequency of the Earth increases inexorably on its way to 2012 and beyond.

In 1951, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,326,543. This was a low year.

From 1952 to 1955, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 59.6%, from 11,266,129 to 4,549,106.

From 1952 to 1955, the 59.6% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 9.6% less than its 65.9% decrease from 1947 to 1949.

However, from 1952 to 1955, the 9.6% negative variance in the decrease of the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon vs. 1947 to 1949 was 71.8% less than the 34.1% negative variance from 1947 to 1948 vs. 1943 to 1944.

From 1952 to 1955, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 59.6%, from 11,266,129 to 4,549,106.

From 1952 to 1953, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 45.7%, from 11,266,129 to 6,111,500.

In 1952, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,266,129.

From 1953 to 1954, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 23.8%, from 6,111,500 to 4,652,625.

In 1953, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 6,111,500.

From 1954 to 1955, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 2.2%, from 4,652,625 to 4,549,106.

In 1954, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,652,625.

From 1955 to 1956, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 95.2%, from a low-year 4,549,106 to 8,881,467.

From 1955 to 1956, the 95.2% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 40.6% less than the 160.4% increase from 1951 to 1952.

Television is in full-swing, and its degradation of the ether is decreasing the fertility of salmon in Alaska here in the early 1950’s.

In 1955, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,549,106. This was a low year.

From 1956 to 1958, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 66.4%, from 8,881,467 to 2,985,666.

From 1956 to 1958, the 66.4% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 11.4% greater than its 59.6% decrease from 1952 to 1955.

Technology is getting ever-stronger, and is pushing the fertility of salmon in Alaska backward, toward extinction.

From 1956 to 1957, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 29.3%, from 8,881,467 to 6,275,502.

From 1956 to 1957, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 30%, from 26,239,044 to 18,358,288.

From 1956 to 1957, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay increased by .9%, from 33.8% to 34.1%.

In 1956, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 26,239,044.

In 1956, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 8,881,467.

In 1956, the 8,881,467 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 33.8% of the total run of 26,239,044.

From 1957 to 1958, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 52.4%, from 6,275,502 to 2,985,666.

From 1957 to 1958, the total run of Bristol Bay salmon decreased by 65.8%, from 18,358,288 to 6,275,592.

From 1957 to 1958, the 65.8% decrease in the total run of Bristol Bay salmon was 25.6% greater than the 52.4% decrease in salmon caught.

From 1957 to 1958, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay decreased by 25.2%, from 34.1% to 25.5%.

In 1957, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 18,358,288.

In 1957, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 6,275,502.

In 1957, the 6,275,502 salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 34.1% of the total run of 18,358,288.

From 1958 to 1960, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 359%, from 2,985,666 to 13,705,002.

From 1958 to 1960, the 359% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 277% greater, or nearly four times greater than its 95.2% increase from 1955 to 1956.

2012, the last year of the Mayan “long count”, is getting closer and closer. The increasing energy frequency of the Earth and the increase in health of the ether which attends it are becoming more and more visible in these statistics.

From 1958 to 1959, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 54.3%, from a low-year 2,985,666 to 4,608,199.

From 1958 to 1959, the 54.3% increase in the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon was 43% less than its 95.2% increase from low-year 1955 to 1956.

From 1958 to 1959, the 43% negative variance in the increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay salmon versus 1955 to 1956 was 5.9% greater than the 40.6% negative variance from 1955 to 1956 vs. 1951 to 1952.

From 1958 to 1959, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay increased by 35.1%, from 25.5% to 34.2%.

In 1958, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 6,146,052.

In 1958, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 2,985,666. This was a low year. This is the fifth-lowest catch in the data set, just ahead of 1896’s 1,999,740.

In 1958, the 2,985,666 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 25.5% of the total run of 6,146,052.

From 1959 to 1960, the total Bristol Bay sockeye salmon run increased by 197.6%, from 13,486,569 to 40,136,345

From 1959 to 1960, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 197%, from 4,608,199 to 13,705,002.

From 1959 to 1960, the 197% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 263% greater that its 54.3% increase from 1958 to 1959.

From 1959 to 1960, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay decreased by .3%, from 34.2% to 34.1%.

The Fish Feds are managing this shit to the gnat’s eyelash.

The trends which I am elucidating are the variables.

In 1959, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 13,489,569.

In 1959, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,608,199.

In 1959, the 4,608,199 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 34.2% of the total run of 13,489,569.

From 1960 to 1963, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 79%, from a high-year 13,705,002 to a low-year 2,871,136.

From 1960 to 1963, the 79% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 19% greater than its 66.4% decrease from 1956 to 1958.

From 1960 to 1961, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 39.6%, from 40,136,345 to 24,244,953.

From 1960 to 1961, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 18.3%, from a high-year 13,705,002 to 11,191,326.

From 1960 to 1961, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay increased by 23.8%, from 34.1% to 42.2%.

In 1960, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 40,136,345.

In 1960, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 13,705,002.

In 1960, the 13,705,002 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 34.1% of the total run of 40,136,345.

From 1961 to 1962, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 57.8%, from 11,191,326 to 4,718,016.

From 1961 to 1962, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay decreased by 10.4%, from 46.2% to 41.4%.

In 1961, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 24,244,953.

In 1961, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 11,191,326.

In 1961, the 11,191,326 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 46.2% of the total run of 24,244,953.

From 1962 to 1963, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 39.1%, from 4,718,016 to 2,871,136.

From 1962 to 1963, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 30.5%, from 11,383,354 to 7,905,616.

From 1962 to 1963, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay decreased by 12.3%, from 41.4% to 36.3%.

In 1962, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 11,383,354.

In 1962, the commercial catch of Br!stol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,718,016.

In 1962, the 4,718,016 sockeye salmon caught in the commercial Bristol Bay run comprised 41.4% of the total run of 11,383,354.

From 1963 to 1965, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 745%, from a low-year 2,871,136 to a high-year 24,255,239.

From 1963 to 1965, the 745% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 107.5% greater, or more than twice as great as its 359% increase from 1958 to 1960.

As you can see, poor Mother Gaia is not dying so much, here in the hand-writing folk rock era of the early to mid 1960’s.

From 1963 to 1964, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 94.9%, from a low-year 2,871,136 to 5,596,120.

From 1963 to 1964, the 74.4% positive variance in the increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon vs. low-year 1958 to 1959 was 116% greater, or more than twice as great as the 34.5% positive variance from 1951 to 1952 vs. 1946 to 1947.

From low-year 1963 to 1964, the 94.9% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 74.7% greater than the 54.3% increase from low-year 1958 to 1959.

From 1963 to 1964, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay increased by 35.5%, from 36.3% to 49.2%.

In 1963, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 7,905,616.

In 1963, the commercial catch of 2,871,136 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon comprised 36.3% of the total run of 7,905,616.

In 1963, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 2,871,136. This was a low year.

From 1964 to 1965, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 333%, from 5,596,120 to 24,255,239.

From 1964 to 1965, the percent of the total salmon run caught in Bristol Bay decreased by 17.9%, from 49.2% to 40.4%.

In 1964, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 11,383,354.

In 1964, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 5,596,120.

In 1964, the commercial catch of 5,596,120 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon comprised 49.2% of the total run of 11,383,354.

From 1965 to 1968, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 88.4%, from a high-year 24,255,239 to a low-year 2,792,849.

From high-year 1965 to low-year 1968, the 88.4% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 11.9% greater than its 79% decrease from high year 1960 to low-year 1963.

The health of the ether is degrading, going forward in time.

From 1965 to 1966, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 61.6%, from a high-year 24,255,239 to 9,314,240.

From 1965 to 1966, the 61.6% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 236.6% greater than its 18.3% decrease from high-year 1960 to 1961.

In 1965, the total run of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 60,071,505.

In 1965, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 24,255,239.

In 1965, the commercial catch of 24,255,239 Bristol Bay sockeye salmon comprised 40.4% of the total run of 60,071,505.

From 1966 to 1967, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 53.5%, from 9,314,240 to 4,330,730.

In 1966, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 9,314,240.

In 1967, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,330,730.

From 1968 to 1970, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 642%, from a low-year 2,792,849 to a high-year 20,720,766.

From low-year 1968 to high-year 1970, the 642% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 13.8% less than the 745% increase from low-year 1963 to high-year 1965.

The health of the ether is degrading, going forward in time.

From 1968 to 1969, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 137%, from 2,792,849 to 6,621,698.

From low-year 1968 to 1969, the 137% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 44.4% greater than its 94.9% increase from low-year 1963 to 1964.

However, from low-year 1968 to 1969, the 44.4% positive variance in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon versus 1963 to 1964 was 40.6% less than its 74.7% positive variance in 1963 to 1964 vs. 1958 to 1959.

From 1968 to 1969, the health of the ether is teetering, just barely increasing.

In 1968, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 2,792,849. This was a low year.

For those keeping score, we’re back down below 1897’s catch of 3,317,523.

From 1969 to 1970, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 212.9%, from 6,621,698 to 20,720,766.

In 1969, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 6,621,698.

From high-year 1970 to low-year 1973, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 96%, from 20,720,766 to 761,322, the lowest in history.

From high-year 1970 to low-year 1973, the 96% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 8.6% greater than its 88.4% decrease from high-year 1965 to low-year 1968.

From 1970 to 1973, the health of the ether decreased to the lowest level in history.

From 1965 to 1968, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 88.4%, from a high-year 24,255,239 to a low-year 2,792,849.

Alaska.gov says “Unfortunately, both the 1969 and the 1970 escapements suffered decreased production apparently because of natural mortality as a result of the extremely cold 1970-1971 winters. Consequently, fishing time was severely restricted in both 1974 and 1975 in order to secure escapement goals for these two critical brood years.”

If you believe that extremely cold winters in the extremely cold waters of Alaska have a negative impact on salmon mortality there, I’ve got a bridge for sale in Brooklyn which I think it might profit you to look at.

From high-year 1970 to 1971, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 53.7%, from 20,720,766 to 9,583,987.

From high-year 1970 to 1971, the 53.7% decrease the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 12.8% less than its 61.6% decrease from high-year 1965 to 1966.

From 1970 to 1971, the health of the ether is improving, going forward in time.

In 1970 , the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 20,720,766. This was a high year.

From 1971 to 1972, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 74.7%, from 9,583,987 to 2,416,233.

In 1971, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 9,583,987.

From 1972 to 1973, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 68.5%, from 2,416,233 to an all-time low 761,322.

In 1972, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 2,416,233

From low-year 1973 to high-year 1976, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 638%, from 761,322, the lowest in history, to 5,619,292, the lowest high year in history.

From low-year 1973 to high-year 1976, the 638% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was .6% less than its 642% increase from low-year 1968 to high-year 1970.

From 1968 to 1970, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 642%, from a low-year 2,792,849 to a high-year 20,720,766.

From 1973 to 1974, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 78.9%, from 761,322, the lowest in history, to 1,362,479.

From low-year 1973 to 1974, the 78.9% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 42.4% less than its 137% increase from low-year 1968 to 1969.

The health of the ether is decreasing, going forward in time.

In 1973, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 761,322, the lowest in history.

In 1973, the 761,322 sockeye salmon caught in Bristol Bay was 19% less than the 940,000 sockeye caught in 1893, the first year that they began keeping records.

From 1974 to 1975, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 259.5%, from 1,362,479 to 4,898,814.

This directly refutes alaska.gov, which stated “Unfortunately, both the 1969 and the 1970 escapements suffered decreased production apparently because of natural mortality as a result of the extremely cold 1970-1971 winters. Consequently, fishing time was severely restricted in both 1974 and 1975 in order to secure escapement goals for these two critical brood years.”

If fishing time was severely restricted in both 1974 and 1975, as alleged by alaska.gov, then how or why could the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon have increased by 260%, or headed toward quadrupled from 1974 to 1975, from 1,362,479 to 4,898,814?

They could not have.

I have exposed the duplicity of the State propaganda organ known as alaska.gov by using what was known in the old days as “fact checking”.

If the Fish Feds in Alaska are so desperate to save the poor salmon, why was fishing time not “severely restricted” after the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 76.8% from 1947 to 1951?

Alaska.gov said “fishing effort was down” during “a period related to World War II”. Why didn’t all of the Alaska salmon fishermen going off to war from 1941 to 1945 explosively increase salmon populations after the war?

As you can see, the folks in charge are not your friends, and are lying to you about basically everything, including the salmon in Alaska.

The Coincidence theorists in the readership are saying “but our environmental knowledge has come so far since then.”

In 1974, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 1,362,479.

In 1975, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,898,814.

From 1976 to 1977, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 13.2%, from a high-year 5,619,292 to low-year 4,877,880.

From high-year 1976 to 1977, the 13.2% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 75.4% less than its 53.7% decrease from high year 1970 to 1971.

The balance has swung back in favor of the ever-increasing energy wavelength of the earth, heading toward 2021, and the increasing health of the ether which attends it.

From high-year 1970 to 1971, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 53.7%, from 20,720,766 to 9,583,987.

In 1976, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 5,619,292. This was a high year.

From 1977 to 1981, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 427%, from a low-year 4,877,880 to a high-year 25,713,212.

From low-year 1977 to high-year 1981, the 427% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 33% less than the 638% increase from low-year 1973 to high-year 1976.

From 1977 to 1978, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 103%, from a low-year 4,877,880 to 9,928,139.

From low-year 1977 to 1978, the 103% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 30.5% greater than the 78.9% increase from low-year 1973 to 1974.

In 1977, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 4,877,880. This was a low year.

From 1978 to 1979, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 115.8%, from 9,928,139 to 21,428,606.

In 1978, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 9,928,139.

From 1979 to 1980, the the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 10.8%, from 21,428,606 to 23,761,764.

In 1979, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 21,428,606.

From 1980 to 1981, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 8.2%, from 23,761,764 to 25,713,212.

In 1980, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 23,761,764.

From high-year 1981 to 1982, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 41%, from 25,713,212 to 15,145,505.

From high-year 1981 to 1982, the 41% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 210% greater, or more than three times greater than its 13.2% decrease from high-year 1976 to 1977.

The ether is degrading at ever-greater rate, going forward in time.

From 1976 to 1977, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 13.2%, from a high-year 5,619,292 to 4,877,880.

From 1981 to 1983, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 45.1%, from an all-time high 25,713,212 to an all-time high 37.3 million.

From 1981 to 1983, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by an annual average of 22.6%.

From 1981 to 1986, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 38.6%, from an all-time high 25,713,212 to 15,776,056.

From 1981 to 1982, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 41%, from an all-time high 25,713,212 to 15,145,505.

In 1981, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled an all-time high 25,713,212. This was a high year.

Alaksa.gov says “The strong sockeye salmon run in 1981 which was not burdened by a price dispute, saw a record harvest of 25.7 million

sockeye salmon that broke the prior record set in 1938 (Table 4).”

Where the uncredited Intelligence operative from the State propaganda organ known as alaska.gov walked the strongest salmon run in history back to merely “strong”, and replaced the specific statistic with the general “broke the prior record”.

In 1982, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 15,145,505.

From 1983 to 1984, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 33.7%, from an all-time high 37.3 million to 24,710,306.

In 1983, the all-time high 37.3 million commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 45.1% greater than the previous record of 25.7 million in in 1981.

From 1984 to 1985, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 5%, from 24,710,306 to 23,474,000.

In 1984, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 24,710,306.

From 1985 to 1986, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 32.8%, from 23,474,000 to 15,776,056.

In 1985, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 23,474,000.

From 1986 to 1987, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 1.4%, from 15,776,056 to 16 million.

In 1986, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 15,776,056.

A current article on wildlife.ca.gov says “From 1987 to 1992, there was a drought in the area. Low flows and a series of fish kills reduced the Mokelumne River steelhead run during the 1980s. In response, EBMUD implemented several programs to improve water quality, flow regimes, and physical habitat in the lower Mokelumne River. The hatchery was remodeled in July 2002, enlarging the rearing space to promote fish health and fish survival rates while also making hatchery operations more efficient.

Since then, the Lower Mokelumme River Fishery Resource has thrived, as evidenced by counts of fall-run Chinook salmon escapement or returning salmon. Returning salmon increased by 3,028 from 1998 to 2003.”

It is a bunch of general claptrap. Yes, they made some improvements, but it is theater, a sideshow. It’s not driving the increases in population.

They’re desperate to keep you from recognizing that the size, fertility, longevity and very existence of any organism vary directly with the health of its etheric environment.

From 1987 to 1988, the 10% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 614% greater than its 1.4% increase from 1986 to 1987.

The reproductive rate of the salmon in Alaska is increasing exponentially, going forward in time.

That’s because the health of the ether is inexorably increasing, and the size, fertility, longevity and very existence of any organism vary directly with the health of its etheric environment.

We’re stepping toward 2012, the end of the Mayan “long count”. And, at this very moment, in the late 1980’s a Manhattan-project-level effort to develop wireless technology which will slow or stop these great positive changes is underway.

From 1987 to 1988, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 10%, from 16 million to 17.6 million.

In 1987, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 16 million.

From 1988 to 1989, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 64.2%, from 17.6 million to 28.9 million.

From 1988 to 1989, the 64.2% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 542% greater, or more than six times greater than its 10% increase from 1987 to 1988.

The reproductive rate of the salmon in Alaska is increasing exponentially, going forward in time.

That’s because the health of the ether is inexorably increasing, and the size, fertility, longevity and very existence of any organism vary directly with the health of its etheric environment.

In 1988, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 17.6 million.

From 1989 to 1990, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 20.5%, from 28.9 million to 34,822,477.

In 1989, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 28.9 million which was the second highest in history, behind 1983’s 37.4 million.

From 1990 to 2010, the Mokelumne River Chinook redd salmon count averaged 710.

From 1990 to 1997, Chinook salmon redds in the lower Mokelumne River increased by 1,754%, from 71 to 1,316.

From 1990 to 1991, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 21.6%, from 33,444,000 to 26,233,469.

From 1990 to 1991, the 21.6% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 35.9% less than its 33.7% decrease from 1983 to 1984.

The health of the ether is improving, going forward in time.

In 1990, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 33,444,000.

From 1991 to 1992, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 23.2%, from 25,821,000 to 31,800,000.

From 1991 to 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds decreased by 42.3%, from 71 to 41.

From 1991 to 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns decreased by 39.7%, from 68 to 41.

From 1991 to 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners decreased by 14%, from 429 to 369.

In 1991, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 25,821,000.

In 1991, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 429.

In 1991, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 68.

In 1991, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 71.

From 1992 to 1998, the Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery return increased by 15,717%, from 41 to 6,485.

From 1992 to 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns increased by 1,634%, from 41 to 711.

From 1992 to 1993, the 154.3% increase in Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds was 464% greater than their 42.3% decrease from 1991 to 1992.

From 1992 to 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 154.3%, from 127 to 343.

From 1992 to 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners increased by 153%, from 369 to 934.

From 1992 to 1993, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 15.9%, from 37,967,121 to 31.9 million.

In 1992, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 31,880,000.

In 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 369.

In 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 127.

In 1992, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 41.

From high-year 1993 to 1994, the 12.9% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 40.3% less than the 21.6% decrease from high year 1990 to 1991.

From 1993 to 1994 vs. 1990 to 1991, the 40.3% negative variance in the decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 12.3% greater than ts 35.9% decrease from 1991 vs. 1983 to 1984.

The health of the ether is increasing, going forward in time.

From 1993 to 1995, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 10.5%, from 40,463,000 to an all-time high 44.7 million.

From 1993 to 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns increased by 204%, from 711 to 2,164.

From 1993 to 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 54.5%, from 343 to 530.

From 1993 to 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners increased by 6%, from 934 to 993.

From 1993 to 1994, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 12.9%, from 40,463,000 to 35,224,000.

In 1993, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 40,463,000 million.

In 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 934.

In 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 711.

In 1993, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 343.

From 1994 to 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners increased by 51.4%, from 993 to 1,503.

From 1994 to 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 46%, from 530 to 774.

From 1994 to 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns decreased by 11.4%, from 2,164 to 1,918.

Naturally-spawning salmon are doing great, and hatchery returns are decreasing. Why?

From 1994 to 1995, the 11.4% decrease Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns was 105% less than their 204% increase from 1993 to 1994.

In 1994, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 35,224,000.

In 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 2,164.

In 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 993.

In 1994, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 530.

From 1995 to 1998, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 78.3%, from an all-time high 44.7 million to 9.7 million.

Here we see a fantastically successful debut for the literal forest of what we collectively refer to as “wireless communications infrastructure” which was thrown up suddenly virtually overnight in every city, town and village on Earth in the mid to late 1990’s.

The Bristol Bay Fishermen’s Association said that it was because “large numbers of salmon” were “being stolen on the high seas”.

In the Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin, the University of Alaska, Fairbanks’ Gordon H. Kruse said it was because of “Anomalous Ocean Conditions”, by which he meant very calm and sunny weather.

From 1995 to 1998, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by an annual average of 26.1%.

From 1995 to 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns increased by 73%, from 1,918 to 3,323.

From 1995 to 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners increased by 39.3%, from 1,503 to 2,094

From 1995 to 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 14.7%, from 774 to 888.

From 1995 to 1996, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 35.1%, from an all-time high 44.7 million to 29 million.

From high-year 1995 to 1996, the 35.1% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 144.1% greater than its 12.9% decrease from high-year 1993 to 1994.

Here, with “cell phone towers” springing up virtually overnight in every city, town and village on Earth, there has been a sudden, gigantic decrease in the health of the ether.

From 1993 to 1994, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 12.9%, from 40,463,000 to 35,224,000.

In 1995, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was an all-time high 44.7 million.

In 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 1,918.

In 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 1,503.

In 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 774.

In an article from 2008, the California Sportsfishing Protection Alliance’s webmaster, Jerry Neuberger said “In the mid-1990’s, a series of late summer warm water releases from Camanche Dam killed almost all of the trout and steelhead below the dam. Hundreds of fish could be seen floating down the river from Van Assen Park to Clements, ten miles away. An agreement was made that provided water for the salmon in the Mokulemne River and at the same time delivered flows for farmers and other uses during the various water years from Wet down to Critically Dry. Improvements were made to the fish ladder at Woodbridge Dam, the water release mechanism at Camanche Dam and the spawning gravel in in the river between Woodbridge and Van Assen Park. Salmon returns skyrocketed.”

Jerry is outlining an Op which involved all of the only-generally-described improvements which he mentions, however those machinations are not what caused salmon populations in the river to only-generally “skyrocket”.

As a propagandist, Jerry knows that many or most readers will grasp virtually any straw, no matter how thin, to remain off the hook of personal responsibility.

Since we’re studying the subject in a scholarly way, we know that, from 1994 to 1995, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns decreased by 11.4%, from 2,164 to 1,918.

Sorry, folks, but Jerry’s lurid “hundreds of fish could be seen floating down the river” is a bald-faced lie.

I have exposed the duplicity of the California Sportsfishing Protection Alliance and their webmaster jerry Neuberger by using what was known in the old days as “fact checking”.

From 1996 to 1997, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners increased by 85.8%, from 2,094 to 3,892.

From 1996 to 1997, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 44.6%, from 888 to 1,284.

From 1996 to 1997, Chinook redd salmon in the Mokelumne River increased by 2.5%, from 1,284 to 1,316.

From 1996 to 1997, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 43.9%, from 29,592,000 to 12,100,000.

In 1996, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 29,592,000.

A current What To Think article on Bristolbayfishermen.org is headlined “Salmon Interception Issues”.

Where “Salmon interception issues” is Mil-speak for “low-wavelength microwave radiation kills salmon”.

The uncredited author goes on to say “The first sign of troubles for the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon run was in 1996. Fishers in Bristol Bay were pleased with a nearly 30 million sockeye harvest, but the Kvichak River inexplicably missed its 4 million escapement goal by 2.5 million fish.

Government officials have tried to reassure Western Alaskan fishers that large numbers of salmon are not being netted in international waters. We at BBFA agree that due diligence by U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards has prevented large numbers of salmon from being stolen on the high seas.

An extensive fishery was quietly initiated inside Russian waters by Japanese driftnet vessels in the 90’s. This fishery has resulted in a one-two knockout punch for fishers and communities in Bristol Bay and Western Alaska. Bristol Bay drift permitholders on average thousands of dollars of income, and losses in value of vessels and permits since 1996.”

This propaganda masks the fact that low-wavelength microwave radiation was decimating the salmon in the Pacific.

David Milholland states, “The downturn of the fisheries in Bristol Bay starting in the last half of the 90’s has not been adequately explained by any scientific proof. The increasing pressure on salmon stocks within the Russian 200-mile zone, by the Japanese fleets and others, no doubt, is part of the reason for the decline of the sockeye in Bristol Bay in the minds of knowledgeable fishermen.”

Here, in the late 1990’s, we’re well into a digital world where videos of huge fleets of felonious salmon fishing boats would be splashed across the internet, regardless of how corrupt the news networks obscuring the event were.

The fact that David brazenly states “has not been adequately explained by any scientific proof” hides the scientific truth that low-wavelength microwave radiation kills salmon.

He generally intones that “knowledgeable fishermen” are with the program, and believe his line of inexplicable bullshit. As indeed, they do, as they earnestly listen to him lie bald-facedly.

Here’s David Milholland’s picture, where the image is constructed to focus attention on his left eye:

(Fisherman David Milholland, who said that the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 78.3% from 1995 to 1998, from an all-time high 44.7 million to 9.7 million, because of “increasing pressure on salmon stocks”, “by the Japanese fleets and others”.)

The image is constructed to focus attention on his left eye because, to generational Satanist Freemasons like David, the left eye is the “eye of Will” or the “eye of Horus”.

But don’t take my word for it:

‘The right eye is the Eye of Ra and the left is the Eye of Horus’.”

From “Freemasonry - Religion And Belief - The 3rd Temple”

Facebook: “Welcome to the Left-Hand-Path-Network, where Satanism is not about worship, but it’s study.”

I have included David’s picture so that you could get a better idea of what a generational Satanist Freemason in a position of marginal influence looks like.

He figured that the rubes would never notice the coded visual imagery.

It’s not like these people aren’t right up front about what they’re doing, and what they’re into.

We’ve just been conditioned, over literally Millennia, not to “notice” it.

Generational Satanists are all related to one another through the maternal bloodline. They comprise between twenty and thirty percent of the populace, and are hiding in plain sight in every city, town and village on Earth.

It’s how the few have controlled the many all the way back to Babylon, and before.

But they say that the hardest part of solving a problem is recognizing that you have one.

Don Croft used to say “Parasites fear exposure above all else”.

How long do you think that these people have left in power, now?

Please consider doing what you can to help speed the transition.

In 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 2,094.

In 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 3,323.

In 1996, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 888.

From 1997 to 1998, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds increased by 2.4%, from 1,316 to 1,284.

From 1997 to 1998, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners decreased by 6.9%, from 3,892 to 3,624.

Here, from 1997 to 1998, after five straight years of a burgeoning naturally-spawning salmon numbers in the Mokelumne River, we have a sudden decrease in that population. Why?

From 1997 to 1998, the Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery return increased by 67%, from 3,883 to 6,485.

In 1997, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 12,100,000.

Forecast error, measured as the percent deviation between actual and forecasted runs, was -74.6%, the second largest departure on record (since 1961). Actual catch in 1997 was 49% of forecasted catch.

Here’s the Bristol Bay Fisherman’s Association on 1997: “We have yet to see any body of evidence that climate or weather is the key cause of the mortality of millions of salmon. The public has been dished up plate after plate of weather and climate fodder that has been used to try to explain the mortality of millions of salmon. Most notable and hard to digest, was the 1997 theory that 13 million salmon died between Port Moeller and Bristol Bay due to very calm and sunny weather.”

In 1998, the Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin published the University of Alaska, Fairbanks’ Gordon H. Kruse’s “Salmon Run Failures in 1997-98: A Link To Anomalous Ocean Conditions?”

Where “anomalous” is an example of the propaganda technique known as “stonewalling”.

In 1997, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 3,892.

In 1997, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 3,883.

In 1997, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 1,284.

From 1998 to 2010 the Mokelumne River Chinook redd salmon count of 748 was 5.3% greater than its average of 710 from 1990 to 1997.

The ether is improving, going forward in time.

From 1998 to 2010, the Mokelumne River Chinook redd salmon count averaged 748.

From 1998 to 1999, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 164%, or well more than doubled, from 9,700,000 to 25,660,000.

From 1998 to 1999, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River decreased by 26%, from 7,213 to 5,335.

In 1998, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 9,700,000, which was 47% of the forecasted catch.

In 1998, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon hatchery returns totaled 6,485.

In 1998, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon natural spawners totaled 3,624.

In 1998, Mokelumne River fall-run Chinook salmon redds totaled 1,316.

From 1999 to 2000, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River increased by 39%, from 5,335 to 7,418.

From high-year 1999 to 2000, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 20.2%, from 25,660,000 to 20,469,000.

From high-year 1999 to 2000, the 20.2% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 73.7% less than its 35.1% decrease from high-year 1995 to 1996.

The health of the ether is improving, going forward in time.

In 1999, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 25,660,000.

In 1999 5,335 salmon returned to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River.

From 2000 to 2002, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 48.2%, from 20,469,000 to 10.6 million.

From 2000 to 2002, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by an annual average of 24.1%.

From 2000 to 2001, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River increased by 9.4%, from 7,418 to 8,114.

From 2000 to 2001, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 30.7%, from 20,469,000 million to 14,181,000.

From 2000 to 2001, the 30.7% decrease in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 26.8% greater than its 24.2% decrease from 2001 to 2002.

The health of the ether is improving, going forward in time.

In 2000, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled totaled 20,469,000.

In 2000, 7,418 salmon returned to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River.

From 2001 to 2002, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon decreased by 24.2%, from 14 million to 10.6 million.

In 2001, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled totaled 14,181,000.

In 2001, 8,114 salmon returned to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River.

From 2002 to 2003, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 43%, from 10,678,568 to 15,277,000.

In 2002, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon totaled 10,678,568.

From 2003 to 2004, the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon increased by 60.4%, from 15,277,000 to 24,498,000.

From 2002 to 2003, the 60.4% increase in the commercial catch of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon was 40.5% greater than its 43% increase from 2002 to 2003.

The health of the ether is improving, going forward in time.

In 2002, 10,757 salmon entered the Mokelumne river above Woodbridge Dam.

From 2002 to 2003, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River decreased by 4.8%, from 10,757 to 10,241.

From 2003 to 2006, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River decreased by 42.9%, from 10,241 to 5,839.

From 2003 to 2006, the salmon return to the hatchery on the Mokelumne River decreased by an annual average of 14.3%.

From 2003 to 2006, the 14.3% average annual decrease in the return to the salmon hatchery on the Mokelumne River was 198% greater than its 4.8% decrease from 2002 to 2003.